JANUARY – FEBRUARY 2019

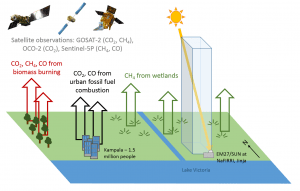

A guest post from MOYA’s sister project, ZWAMPS. Photos and text by Trish and Tim Broderick

Trish and Tim Broderick flew Emirates to Lusaka from Harare on the evening of Sunday 27th January 2019. They were met at the airport by Abby, a very friendly and pleasant man, from the car hire company. We settled comfortably into the Cresta Golfview Hotel along the Great East Road, which was to be our home for the next couple of weeks.

The original intention had been to drive from Harare, with camping kit loaded. However, the chaos over the economic situation and the resulting hours-long queues for fuel made it impractical, and we did not know if fuel would be available for the return journey. As it turned out we would not have needed the camping kit.

28th Jan: The following morning, having received the hire car, we set out for the Geological Survey. We had a problem: Tim only had very old maps of Lusaka city, which has grown and changed over the years. We did try to buy an up to date map, but were either told they had not been printed or were out of stock. The exciting part of this, for Tim, was driving in Lusaka traffic using an automatic car for the very first time! Trish kept a hand on his left leg and whenever his muscles tightened, as if to seek the clutch, she squeezed hard to remind him not to do that!!

It turned out to be a very long morning as we were ‘Lost in Lusaka’. Tim believed that, as part of the Ministry of Mines, the Geological Survey was incorporated in the same building. However, it seemed that both had moved from the original location as per his map! Eventually, finding the Ministry at its new location in the Government Complex, parking and finding someone to talk to on the 14th floor, a kind staff member drew us a map and we set off again. Closely following the instructions we went wrong again and ended up at the gates of the Zambian Air Force Headquarters!! Finally a gate guard nearby insisted on getting into our vehicle to conduct us to the right place… and there it was. Francis Chibesakunda, the Chief Hydrocarbon Officer said he’d been expecting us all morning and it was now past 2 o’clock. Meanwhile our daughter in Harare had been following our adventures with some amusement and had offered to help find the way from her phone. That would have been fine if we’d had a physical address!! At last Tim was able to settle down to make arrangements with Francis, and we met the rest of the Hydrocarbon team, who were very interested and already well informed about the task ahead. Young Musa Lambakasa, the new Environmental Officer, was assigned to us and we made arrangements for the next day. That was to be, on Euan’s suggestion, a visit to the Chunga dumpsite north of the city! During the day we’d found time to visit a local shopping mall where we bought gumboots, which proved very necessary on the trip.

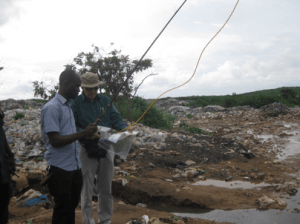

29th: The next morning after an excellent breakfast at the hotel we set out to pick up Musa and made our way to the dump. It is huge and phew, what a smell that invaded one’s nostrils and lasted after we left. Tim had looked on Google Earth at images of the dump and could see the direction of a smoky plume carried by the prevailing wind, so, the plan was to take air samples more or less along the path of the plume and finally upwind for the control. As Tim was training Musa in the art of air catching, a guard came along and insisted that we required permission from his superior, a lady, as it turned out. We were quite surprised that there were guards, all in radio contact, but it seemed that they act as some kind of control of the dumping and scavenging for recyclables that takes place. Aside from being delaying, and averting a need for a letter of authority from the Municipality, there was no problem as Musa displayed his diplomatic talents that we came to rely on all the days we were in Zambia. Trish’s photos show the progress of the air samples through the dump until we reached a cemetery and finally burgeoning high-density settlement (Fig. 1-3). Consulting his out of date map, Tim decided on a spot in a ‘mealie field’ where we could take a control sample. Well, and of course, the place chosen was totally built up with small dwellings, vendors and crowds of people (Fig. 4). Eventually a spot was found where the control sample could be taken. That ended our work for day one!

Fig 1: Chunga Dump, Lusaka

Fig 2: Musa learns to catch air

Fig 3: Downwind plume from Chunga Dump

Fig 4: Searching for a control point!

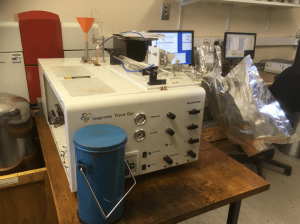

30th Jan: The Ngwerere River foray. The next day we collected Musa and set out on the airport road for an apparent reed bed identified on Google Earth. Tim’s difficulty was to find any suitably open sites within reach of Lusaka, now a city with over 2.5 million inhabitants. On the way Musa received a phone call instructing us that the FAAM BA146 had arrived with the party of scientists from Entebbe, from where the first phase of the operation had taken place across Uganda. We were asked to meet them as the welcoming party as the plane was parked at the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) hardstand (Fig. 5) where we were to find the presiding major. This took some time as the crew had been bussed to the airport for immigration formalities. Eventually scientists and crew came through the doors and we were able to make some brief introductions before they made their way to the hotel and we continued to the Ngwerere River. This was only after an altercation over a suggested fine for parking in the VIP slot, to which we were directed, but which was skilfully negotiated to zero by Musa. Once we had crossed the river bridge and assessed the presence of an extensive reed bed (Fig. 6), Tim chose spots for sampling along the wooded and cultivated roadside. Working backwards to the source target, we achieved a suitable sample suite, including the control point. Musa was requested to return to the CAA office, whereupon we were invited to take a preview of the plane. That was a privileged moment and Musa’s excitement, for one, could not be suppressed, especially given the barrage of instrumentation encountered. Tim then dropped Trish back at the hotel before fighting the intensely congested traffic to take Musa back to a point where he could find transport home. The evening was spent getting to know some of the scientists and crew, particularly Mo (Maureen Smith), who had done most of the pre-expedition organising.

Fig 5: Preview of FAAM G-Luxe

Fig 6: The Ngwerere reed bed

31st Jan: This was a day when Trish rested, recovering from flu, it was a welcome relief. Tim and James France from Royal Holloway, went to the Geological Survey to order maps and reports and to the nearby Surveyor-General for topographic map coverage. This took up most of the morning. Dave Lowry arrived at mid-day and, as the airport shuttle had failed, Tim and James went to pick him up at the airport. Then it was back to the Survey to introduce Dave to the counterparts and to pick up maps.

That day Dave Simpson in particular was running around trying to finalize the necessary military authorization for the intended flights. The signature came the next morning, so the sorties could go to schedule.

There had been talk of our going to Lake Bangweulu, by road, but in discussion it was realised that this venture was too ambitious for the time available. It is a ten-hour drive from Lusaka to any suitable place to stay and the area is so large that it would require at least six days there to do the job justice. Later our experiences of distance and disaster made us realise that it is a trip that has to be very well thought out. It would be better to go in more than one vehicle with a team that would add security in the event of any mishap. We would also have to ensure that the tools in the car, especially the jack, are suitable for all conditions. Mike Daly recommended that we acquire a satellite phone as one is often out of range of a cell phone signal. We are thinking of July or August, probably during the Zimbabwe school holidays for that excursion, as it will mean that our photographer daughter might be available.

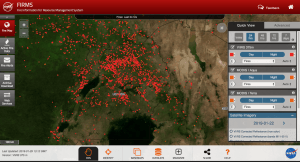

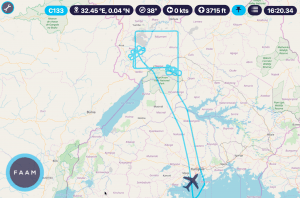

1st Feb: The day’s sortie covered Lake Bangweulu and adjacent swampland, returning along the Luangwa and Muchinga rift escarpments in the hopes of picking up helium anomalies relating to hot springs. James was on this flight filling Tedlar bags for all he was worth. With Dave Lowry we collected air in the hotel grounds near the golf course, which we could not see, but impala graced the lawns.

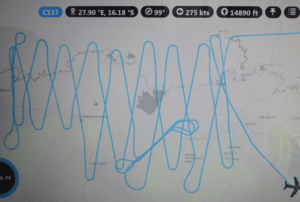

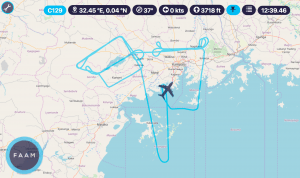

2nd Feb: This was an exciting day for Tim as he had missed the Bangweulu flight the day before. This time they zig-zagged across the Kafue Flats, and the Lochinvar hot springs. Trish again stayed back at the hotel and enjoyed watching the plane’s progress from the Ops Room, which had been set up in the hotel conference centre. This was Musa’s first ever flight and he had the privilege of sitting with Stefan as his mentor. It was a great experience for Tim and for Senior Geologist, Everisto Kasumba, to view the intimate detail of the flood plain, its dynamics and to follow the progress and view the data acquisition in real time. A real Wow!

In the afternoon we shopped with Dave and Stephan, who needed gum boots, and we had to stock up with snacks and drink for the next day’s adventure.

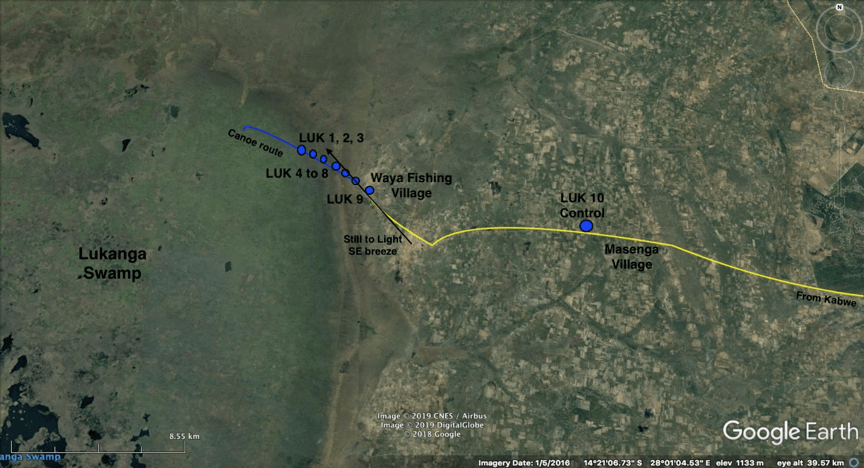

3rd Feb: This was the day we drove to the Blue Lagoon along the Mumbwa Road while the plane flew its ‘Union Jack’ survey over the Lukanga Swamp. Dave Lowry has written this section up for the blog along with our eventful trip to Mazabuka on 5th. Meanwhile the plane landed safely on return from Lukanga, but then a problem arose with the wing flaps meaning that the flight, planned to obtain profile samples over Lusaka before refuelling for their onward return to Entebbe, had to be cancelled. This was a disappointment for some of the Geological Survey people who had been invited on the flight, but especially for the flight engineers. In order to make repairs to what was thought to be a software problem, parts had to be flown out from the UK. It all worked out and the plane was able to return to Entebbe

4th Feb: Not knowing how long the delay would be most of the scientific contingent, including Mo, departed on commercial flights via Entebbe and then onward to the UK. With pilots exchanged ex Entebbe and the problem solved, the plane was flown to Entebbe for final logistical arrangements before returning to England.

Meanwhile, Tim discovered that a puncture had developed on the hire car during the night and the right rear wheel had to be changed. This was repaired at a nearby roadside facility, and the vehicle was badly in need of a wash. Then with brake fluid leaking everywhere, the car hire people had to be called in, and it took the remainder of the day to obtain a replacement vehicle. All was well that ended well. It was fortuitous that this all happened whilst in Lusaka.

5th Feb: Mazabuka and the blow-out. Due to the lost day in Lusaka there was no time for Dave, James, Musa and the Broderick’s to venture forth, overnight in Monze and join Mike Daly to witness his sampling of the Bwanda and Gwisho hot springs in Lochinvar National Park, the site of a geothermal energy investigation south of the Kafue. Mike was there to sample the emitted gasses in flasks for their helium content. He measured temperatures in the order of 90oC in the eyes of these springs.

Dave Lowry has penned an account of our adventures to Mazabuka and thence to the Nenga pump station close to the Kafue and beyond the sugar plantations where we were able to take a suite of air samples.

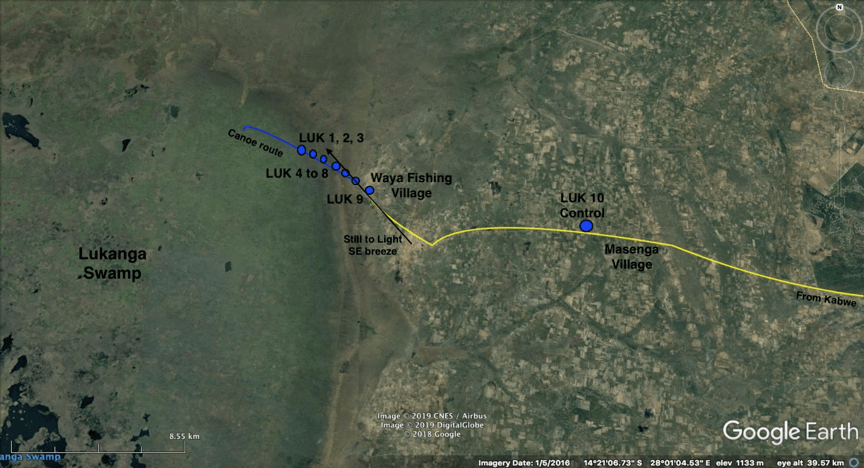

6th / 7th Feb: Dave and James departed for the UK on 6th whilst the FAAM crew with their BA146 reached Entebbe. Musa, Trish and Tim then drove the replacement Pajero to Kabwe and booked in at the Broken Hill Lodge for the night. We were aiming for the Lukanga swamp and by dint of trial and error, local questioning, GPS and our map managed to find the right road, which we tried out that afternoon. In the wake of the previous night’s rain, this proved to be a very rutted, ponded and muddy road made feasible by its laterite base. We got about half way to Chilumba School, but had developed the confidence that we could make the remaining distance to Waya Fishing Village, despite the gruelling 4 x 4 driving required in the face of a stream of charcoal-bearing bicycles, ox carts, motor cycles and the occasional vehicle (Fig. 7). Fortunately it did not rain in the night and we set out early the following morning. The road was appalling and it took hours to navigate, but eventually we arrived at the fishing village where the locals displayed the expected curiosity at our visit. Musa explained what we wanted to do and we confirmed that they had seen the plane traversing the swamp two days before. Welcomed, we set off in the company of the village head and several other friendly fishermen along an elevated dike adjacent to the dredged channel leading into their dugout canoe harbour (Fig. 8). Reaching the swamp margin (Fig. 9), into which we waded to collect our first tedlar samples, the local watched with interest. Eventually as we worked our way back sampling the seasonally inundated wetland and then the termitaria-studded dry zone (Fig. 10), the village head insisted on holding the fishing rod so as to be part of the exercise and of course he had to be in Trish’s photographs! Cattle from the village were grazing in the drier zones along the swamp margin and we took our control sample in the tall mixed brachystegia woodlands back east along the access route. We had to plan the drive back so as to reach Lusaka before dark, which we almost did. From the main road we could see that high rain storm clouds had gathered in the direction of Lukanga Swamp west of Landless Corner and we were very grateful to think that we had not been caught in the wet on that tiresome road. It had been an exhausting time for Tim as he navigated every yard of the road, choosing which way to go and following the most recent tracks of other vehicles.

Fig 7: Charcoal on the road to Lukanga

Fig 8: Trish the ‘bag lady’, Lukanga

Fig 9: The Lukanga Swamp, Waya

Fig 10: Drier grass & termitaria zone, Waya

8th Feb: This was our last day and the first requirement was to get the car washed before we delivered our air bags, aside from those that had gone on the plane, to the Geological Survey to be sent to Euan and Rebecca in Egham by DHL, and also to say our goodbyes to the Director, Francis, Musa and the Survey team. We really hope that Musa will be with us on the trip to Lake Bangweulu, possibly along with James and/or Dave. Following a modicum of shopping, we returned the car in good shape, apart from the fact that we could never release the 4-wheel drive lever. Mike Daly had warned us that he’d never hired a car in Zambia that had not had some mechanical problem. This is why we need to plan the Bangweulu trip so carefully.

Lukanga Swamp Map