Tuesday 29 January

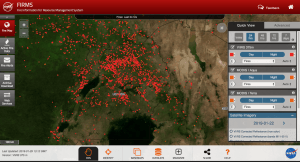

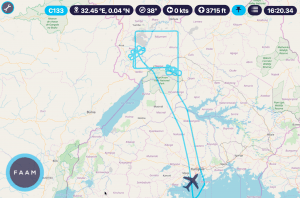

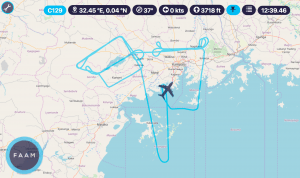

Today’s morning fires survey team are just on their way back from the airport. Yesterday’s flight was great (apart from the fiery temperatures in the cockpit and a very bumpy ride with the strong daytime turbulence/thermals). We sampled a mix of mile-wide flaming and smouldering fire lines in the north of Uganda with varying CH4/CO2/CO ratios and some interesting fire tracers reported from other instruments, sampled by flying along-wind and across-wind at heights between 1000 ft and 6000 ft above ground. We were joined by a couple of flocks of black and white birds at 3000 ft that passed the window rather fast… Much like the Senegal surveys, there was a thick regional haze from the fires and a faint smell of smoke for the whole flight.

We collected bag samples on each pass through the plumes for isotopic analysis and much of the material burning was low-level scrub and papyrus. The land was very dry (much drier than this time last year) and there were many tens of small and large fires in view from the horizon at 3000 ft, most of which appeared to be managed land clearance. The data collected on these flights will improve the knowledge of the isotopic signatures of biomass burning from these plant types in this region, which will better refine models that use isotope measurements as constraints on emission source regions and source types.

By Grant Allen