Without coffee, there is no science

I write this at 8am on a Sunday in a bustling airport in Addis Ababa, with a few hours to spare before my connecting flight. I had intended to prepare a background post outlining the plan for the field work and the wider project, but doing anything non-essential in the run-up to the trip proved a little over-ambitious.

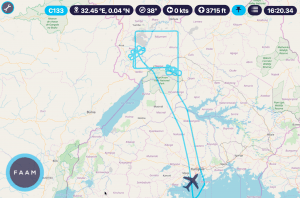

A colleague and I are flying out to Entebbe, which is on Lake Victoria in Uganda, about 30km away from Kampala, to join the rest of the detachment team to work on the FAAM research aircraft. We took a red-eye flight from London and as a result I really needed the excellent Ethiopian coffee I just finished. We were supposed to start the research flights tomorrow, but the final sign off has not yet been obtained from the local officials – not for want of trying! So instead, today is a “hard down day”, meaning no access to the research aircraft at all, because without the sign off, we can’t get airborne.

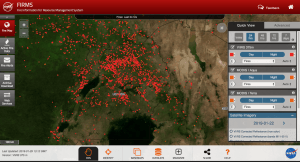

So Monday will be used to get all the instruments up and ready while the aircraft remains on the ground and hopefully Tuesday we will get airborne. We really have a packed schedule, as we are only doing MOYA flights Tuesday to Friday and then one more on Tuesday next week (another project called HyVic is flying over Lake Victoria on the intervening days). The shorter detachment saves on costs, but means we are at the mercy of the weather. To make sure we can fly every day we have several different flight options to choose from: Lake Victoria, Lake Kyoga, Lake Wamala and wildfires in northern Uganda. We will pick one of these based on which location has the best weather conditions, and fingers crossed we have time to do 2 of each. We also hope to circuit Kampala to sample the city’s emissions as part of one of the flights.

Why are we going to all this effort? Mainly to figure out how much methane is coming out from the lakes, wetlands and wildfires. This will help us to piece together the global methane trends – a key factor in how much the planet will warm in the coming years. To do this, we sample the methane in the atmosphere while airborne, as well as ethane and other pollutants. Some of these measurements come in real time, others are taken back to the UK to analyse for carbon isotopes, which gives us a clue as to the emissions source. You will find blogs from our 2017 airborne field work, based in Senegal, where wildfires were sampled. I have to say, based on the turbulence we felt on the commercial flight here, I am not too keen on flying near wildfires (which cause turbulence from their heat) or storms (which are quite common even though this is the dry season for Uganda).

I think the boost from the coffee is wearing off now, so I will sign off from my first post. There will be more content over the coming week, when I hope to have more than a few hours doze before sitting down to write.